11 May Prostate Cancer & Exercise

Written by Curtis Allderidge, Accredited Exercise Physiologist

What is Prostate Cancer?

The prostate is a male sex gland located at the base of the bladder (size of a walnut) and its primary function is to produce seminal fluid. Prostate cancer (PCa) happens when an abnormal growth of the cells in the prostate gland develops (malignant tumour) which is driven by the hormone testosterone. PCa is the second most common cancer diagnosis in men (first is lung cancer) and the fifth leading cause of death worldwide.1

What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Prostate Cancer?

- Frequent urge to urinate, trouble urinating or pain during urination.

- Blood in urine or semen.

- Unexplained pain in lower back, upper thighs, or hips.

- Unexpected weight loss.

How is Prostate Cancer Diagnosed?

The average age of PCa diagnosis is 66 years old.2 Most PCa are detected via elevated levels of Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA). If PSA levels are greater than 4 ng/mL a biopsy will be performed and PCa will be suspected, but not all men with elevated PSA levels have PCa, some mean may have benign prostatic hyperplasia (enlarged prostate) or prostatitis (infection or inflammation of the prostate). If a diagnosis of prostate cancer is confirmed, PSA levels will continued to be monitored during and after treatment to check the effectiveness of the treatment.

Other forms of diagnosis include:

- Digital rectal exam: a doctor is able to feel the size of the prostate and check for any abnormalities.

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): can assess the prostate size and identify any abnormalities as well as where the tumour might be located within the prostate.

- Biopsy: a small surgical procedure where a needle is used to remove multiple small samples of tissue from the prostate gland. The samples are sent to a lab for examination to confirm the presence of cancer.

Prostate Cancer Risk Factors

- Non-modifiable (cannot be changed):

- Age (after the age of 50 years, the odds of developing PCa rapidly increase).

- Family History (having father or brother with PCa doubles risk).

- Ethnicity (African American men have the highest incidence of prostate cancer worldwide and are more likely to develop the disease earlier in life).

- Modifiable (can be changed):

- Obesity (increases insulin resistance and inflammation).

- Diet (increased consumption of animal fat and alcohol, and lower intake of fruits and vegetables).

- Physical activity (increased levels of physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour increase cancer risk).

- Environment (exposure to chemicals and carcinogens).

What Treatments Are Available for Prostate Cancer?

Active surveillance: is a strategy that involves monitoring your prostate cancer closely and choosing to undergo treatment if it advances. It’s an option for men who have *low-risk* prostate cancer.

Radiation therapy:

- External beam radiotherapy: High energy X-ray beams are directed at the prostate, with treatment often performed 5 days per week for 4-8 weeks.

- Internal beam radiotherapy: radioactive material is inserted directly into the prostate which releases concentrated amounts of radiation.

- Side effects:

-

- Fatigue / Tiredness*

- Rectal Bleeding

- Tenderness

- Erectile Dysfunction

- Incontience

- Insomnia

- Weight Loss

- Urinary toxicity

Surgery: Removing the prostate (radical proctectomy) is used to eliminate the cancer when it is confined to the prostate.

Hormone Therapy: Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is considered of the cancer has spread beyond the prostate (aggressive form) and is generally in the form of tablets or injections. Its goal is to reduce the amount of circulating testosterone in the body to slow the growth of the cancer.

- Side effects:

- Fatigue / Tiredness*

- Muscle and strength loss

- Body fat gain

- Lower Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

- Depression

- Hormonal Toxicity

- Erectile Dysfunction

- Gynaecomastia

Chemotherapy: kills cancer cells throughout the body, including those outside the prostate, so it is used to treat more advanced cancer and cancer that did not respond to hormone therapy. Treatment is usually intravenous and is given in cycles lasting 3-6 months.

- Side effects:

- Fatigue / Tiredness*

- Hair Loss

- Nausea

- Mouth Sores

- Peripheral Neuropathy

- Cardiotoxicity

- Cognitive Impairment (Chemo Brain)

- Muscle and Joint Pain

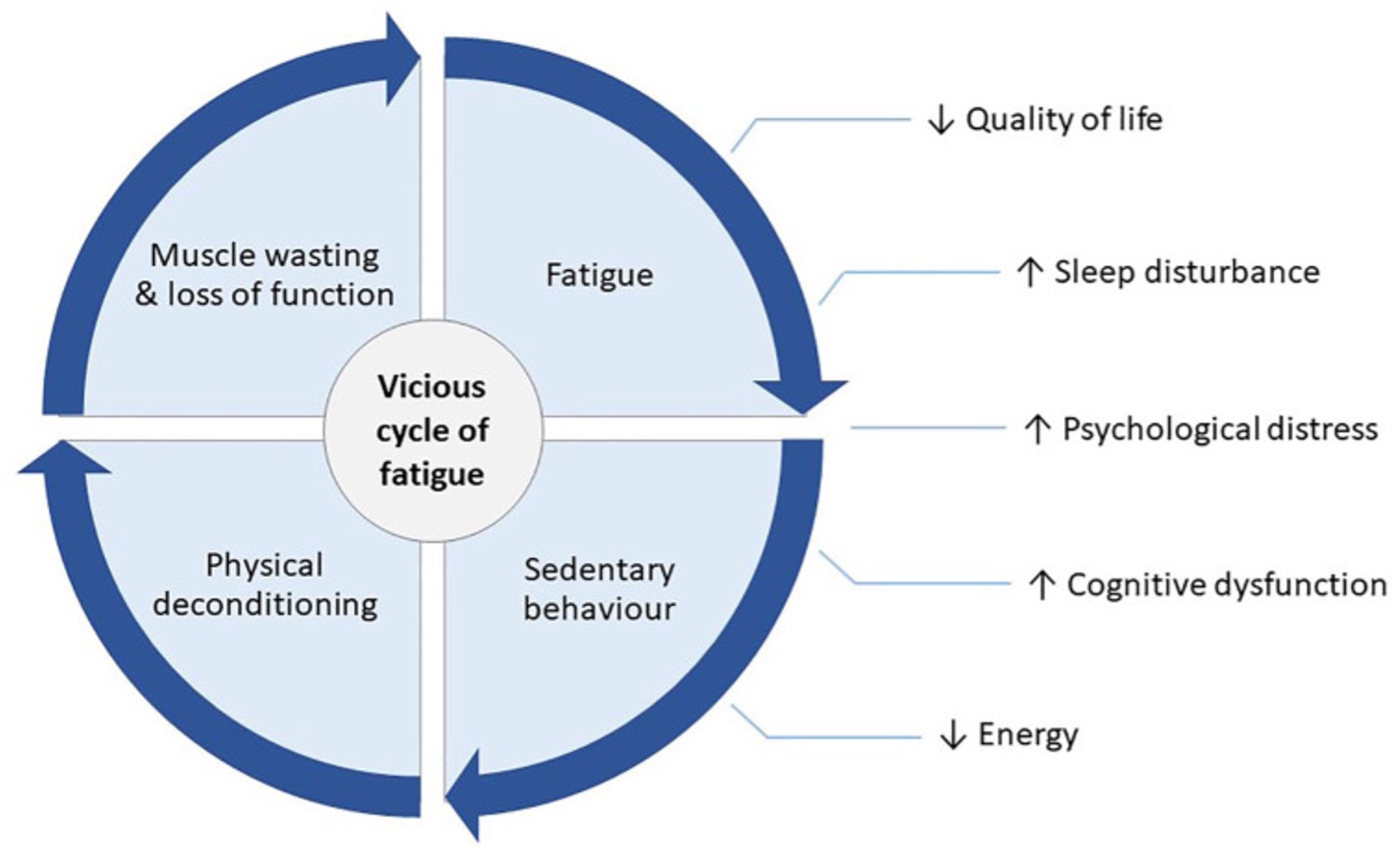

(Picture reference: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7301662/)

How Can Exercise Help?

Unfortunately, cancer treatments come with a vast range of side effects but exercise can thankfully counteract the majority of them! The good news is, prostate cancer patients who commit to an exercise program display lower PSA levels, delay the initiation of ADT by 2 years, experience greater quality of life, less fatigue, and have a lower risk of developing cardiovascular diseases.2

There is evidence that exercise is essentially “medicine” for those on ADT. It addresses several adverse effects such as muscle loss, strength, fatigue, declining physical function, bone loss, and depression/anxiety.3 Recent studies have concluded that exercise is actually more effective at improving Cancer Related Fatigue (CRF) than pharmacological interventions.4

Exercise during chemotherapy and radiotherapy can combat fatigue, cardiotoxicity, muscle weakness, improve body composition, balance, muscle strength, and significantly reduced urinary toxicity (specific radiotherapy treatment side effect).5

How Can an Exercise Physiologist Help?

Exercise Physiology has an essential role in recovery during and post cancer treatment. Not only do Exercise Physiologists provide you with exercise, they can also provide you with education and fatigue management strategies.

Exercise Physiologists will provide an individualised exercise program – that means that each exercise program is different and tailored to a person’s needs and goals. There is not a “one program fits all” for all prostate cancer patients. Each person is undergoing different treatments, will respond differently to exercise, and experiences their own unique side effects from the cancer treatments.

Exercise Guidelines

Progressive Resistance Training:

- 2 days per week

- 8-10 exercise (targeting major muscle groups, especially muscles around the hip and spine)

- 2-3 sets of 8-10 repetitions at a relatively high intensity (70%+ of 1RM)

Weight-Bearing Impact Exercises (i.e., jumping, bounding, hopping, skipping):

- 4 days per week

- 2-4 impact exercises, progressing from a total of 50-100 jumps per session

- Progressive resistance training is recommended before beginning weight-bearing impact exercises

Aerobic Exercises:

- 5-7 days per week

- 30 minutes of continuous training such as cycling, walking, rowing.

- Aerobic training can be broken into 10 minutes blocks spread throughout the day.

Other Things to Consider:

- Pelvic floor Assessment

- Mental health supports

- Dietician

- Support groups

Websites for further information regarding Prostate Cancer:

- https://www.pcfa.org.au/#

- https://www.cancer.org.au/cancer-information/types-of-cancer/prostate-cancer

- https://www.astrazeneca.com/our-therapy-areas/oncology/prostate-cancer.html

- https://australianprostatecancer.org.au/about-prostate-cancer/

References

- Rawla P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J Oncol. 2019 Apr;10(2):63-89. doi: 10.14740/wjon1191. Epub 2019 Apr 20. PMID: 31068988; PMCID: PMC6497009.

- Keogh JW, MacLeod RD. Body composition, physical fitness, functional performance, quality of life, and fatigue benefits of exercise for prostate cancer patients: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012 Jan;43(1):96-110. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.03.006. Epub 2011 Jun 2. PMID: 21640547.

- Edmunds K, Tuffaha H, Scuffham P, Galvão DA, Newton RU. The role of exercise in the management of adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: a rapid review. Support Care Cancer. 2020 Dec;28(12):5661-5671. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05637-0. Epub 2020 Jul 22. PMID: 32699997.

- Mustian KM, Alfano CM, Heckler C, Kleckner AS, Kleckner IR, Leach CR, Mohr D, Palesh OG, Peppone LJ, Piper BF, Scarpato J, Smith T, Sprod LK, Miller SM. Comparison of Pharmaceutical, Psychological, and Exercise Treatments for Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017 Jul 1;3(7):961-968. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6914. PMID: 28253393; PMCID: PMC5557289.

- Lin KY, Cheng HC, Yen CJ, Hung CH, Huang YT, Yang HL, Cheng WT, Tsai KL. Effects of Exercise in Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy for Head and Neck Cancer: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Feb 1;18(3):1291. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031291. PMID: 33535507; PMCID: PMC7908197.

- Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, May AM, Schwartz AL, Courneya KS, Zucker DS, Matthews CE, Ligibel JA, Gerber LH, Morris GS, Patel AV, Hue TF, Perna FM, Schmitz KH. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019 Nov;51(11):2375-2390. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002116. PM

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.